LFINO: Issue #7 - Reading The Recognitions: Chapter 5 - Village Party

'New York is a social experiment' (The Recognitions, I.v)

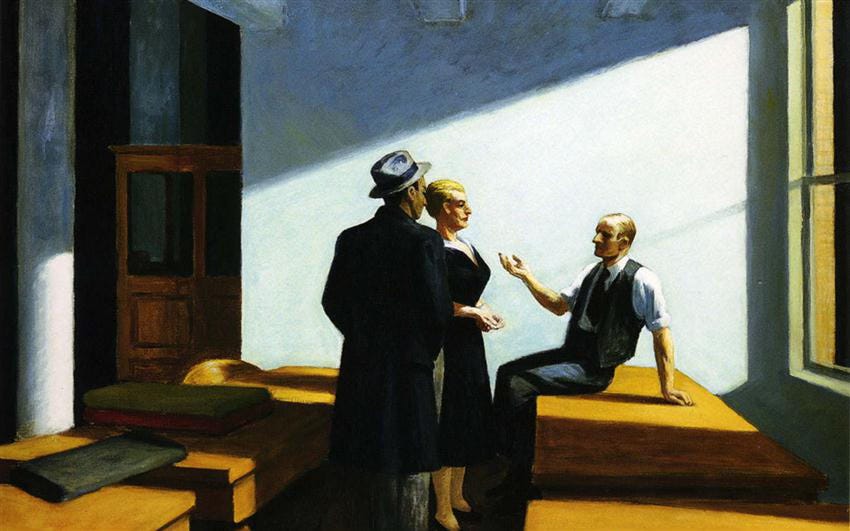

(Edward Hopper, Conference at Night)

Note on the text: This reading of The Recognitions will be using the 2020 New York Review Classics (NYRB) edition of the text. All page number references will refer to this edition. The recommended way to approach this blog is to read the chapter yourself, first, and then come back and read this. Of course you may read it however you like, but I will be starting with a synopsis which will inevitably contain spoilers. This is not intended as a replacement for Steven Moore’s (brilliant) annotations, but as another tool to help unlock this difficult book, and to further add to the discussion of William Gaddis’s work. For specific references, please consult https://www.williamgaddis.org/recognitions/I1anno1.shtml

Synopsis:

Otto returns to New York. Appearing at the apartment of Maude and Arny Munk, he is whisked to a party in the village celebrating the completion of a new painting: L’Ame d’un Chantier. Much of the chapter takes place at this party and it is where we are introduced, or re-introduced, to several characters who we will follow throughout the rest of the novel. It is here that Otto meets the drunken pseduo-mystic Anselm, the organist Stanley, and the heroin-addict artist model Esme. The characters are introduced through their conversations with one another and their reactions to Otto. The chapter is reminiscent of the salon scenes from Marcel Proust’s Guermantes Way and it is consciously aware of this, even making direct references to Proust. Otto is overwhelmed by the sight of Esme across two visual encounters with her. After finally getting his chance to speak to Esme, Otto leaves with her, but not before he is handed a manuscript by a stranger who mistakenly believes that Otto has promised to get published for him. They leave to the ranting disgust of Anselm. No one, for the entire chapter, gives a damn about Wyatt’s arm or his adventure in Central America beyond passing comment.

Characters:

Otto

Maude

Arny

Anselm

Stanley

Esme

Herschel

Adeline

Agnes Deigh

Hannah

Max

Ed

Analysis:

Out of the relative isolation Otto finds himself caught in throughout the previous chapter, Gaddis opens the novel up to a number of new characters which will be significant going forward. It is a chapter which introduces us to the characters of the Village and their favourite pastime, salon parties in someone’s apartment. At its core, the chapter is primarily a vehicle to make the reader aware of characters, their quirks, their goals, and their relationship to Otto (the current ‘protagonist’, for lack of a better term). At first glance the chapter may feel like a small maelstrom of names, unattributed conversation, and shifting action perspective. Yet, aside from a few somewhat obtuse references, particularly from Anselm, the chapter is much more approachable and useful to the narrative than it first appears. What I have come to believe upon thinking on this chapter, is that it is one in which Gaddis gives us a sense of Otto as a subject desiring to be viewed by others and the lengths he goes to in order to (unsuccessfully) control that image.

What must be grasped firmly before anything else can be said of the chapter is how the other characters react, if at all, to Otto. In the unfolding discussion of Otto over the previous two chapters, we have hinted at a conflict between his self-perceived image and how he is actually received by the characters surrounding him. While previously we have only really had Wyatt to compare Otto to, this fifth chapter provides us with a number of similar characters both male and female to test Otto against. If the response and opinions of other characters is essential to understanding where Otto fits into The Recognitions then a facet which can’t be ignored is how he is spoken about by others when he isn’t in the room. Because this chapter begins in the home of Maude and Arny before Otto arrives, we are given a precise look into this.:

- No one’s seen him since that boy Otto…do you remember Otto?

- Otto? Nobody’s named Otto any more, he must be an imposter.

- Herschel, you’ve met him, silly. He used to show up everywhere with Esther before she and her husband… I mean after she and her husband.

- Oh I do remember, Otto. He talked all the time. He was rather cute. Yes, I remember Otto, for almost a year he and Esther made half of a very pretty couple. (171)

This selection of dialogue positions Maude and Herschel’s relationship to our primary cast of characters. Primarily that they know Esther, are seemingly indifferent to Otto, and discuss Wyatt in rumour and innuendo. Otto is referred to as a ‘boy’, as ‘cute’, as ‘an imposter’, as ‘half of a very pretty couple’ and then the question is immediately asked as to whether Herschel even knows who he is despite having met him. The obvious implication is that Otto is a younger man who leaves little impression on that older, hipper crowd. What I believe is also at work here is a sense in which Otto is perceived as incredibly un-serious by the people he chooses to spend his time with. Unlike Wyatt, whose bizarre behaviour clashes with his attempts to disappear, only making him more of a subject of enquiry to the Village dilettantes, Otto isn’t even viewed as an object of curiosity. His relationship with Esther is a curiosity, but more so because Esther is choosing to go with him than anything particularly noteworthy about Otto himself. It is now not enough that the narrative hints at the impotence of Otto’s babbling half-intelligence, but the other characters are directly infantilising him for it. The other question raised by the extract is that Otto is viewed as something of an anachronism. There is something which does not fit, in this instance his name, with the world these characters occupy. ‘He must be an imposter’ is a penetrating critique of a character who seems to approach their pretensions with such serious earnestness. Given what the reader knows about how Otto plans to present himself when he arrives in New York, with the fake injury and the revolutionary antics which caused it, it appears as though he has been immediately seen through before the characters even know they need to see through anything. Although neither party knows it, there is now an implicit sense in the air between the other characters and Otto. The idea of Otto as an ‘imposter’ haunts the reader for the rest of the chapter.

Once Otto does arrive into the chapter, it is clear that other characters don’t particularly care to interact with him in the terms he imposes onto their world. Otto, arriving with his arm in a sling and with a new moustache, is begging to be asked about his time in Central America but no one allows him to elaborate beyond the statement that he has been away. Herschel’s guest, Adeline, herself an outsider in the group dynamic, is completely unimpressed by Otto: ‘And Adeline looked at the golden moustache, and the arm-in-a-sling, and said nothing at all.’ (172) It is easy to argue, especially given the vacuous nature of the conversation the characters in this party engage in, that this is entirely a product of self-interest. Yet, it’s not as though they are acting in such a way that implies they are overlooking Otto. They see him. Adeline, here, actually breaks Otto down into two images, the moustache and the sling, as though that’s all he is. These images, in the description of their separation from Otto, become incongruous. They are artificial images, both. Otto has constructed the moustache and the sling to create the implication of a narrative and to invite speculation. What do these images say? Or, more precisely, what does Otto want them to say? The moustache: maturity and the sense that Otto is older than the ‘boy’ he is. Also, he wants to give the onlooker the impression that, in co-ordination with the sling, that he has been in an exciting situation which has prevented him from having to care about regular grooming. The sling’s meaning is more obvious, it has a direct narrative implicit in its existence: something has happened to me that caused injury; and, in this instance, within it is also the secondary: ask me about it. To Adeline, however, neither of these are compelling enough reason to actually speak to him. Whether she sees through the facade is unclear, but she does recognise the elements which Otto is compelling her to see and ignores it entirely.

Otto is a figure completely trapped in the neurotic presentation of the image, both his, and as we shall see later, and others. This is not a subtle feature of the chapter but it is often moved on from quickly. The obvious instance is when the group arrive at the party and Gaddis provides us with this small hand grenade of character development:

Otto (thinking only of what it looked like to see Otto entering a room) (174)

Otto’s focus is on how Otto is seen by strangers and unknown entities. There’s something about Gaddis’s expression here that positions Otto as believing that his appearance at a party has, or should have, the quality of an event. The fact that he is thinking that his entering a room should look like anything at all betrays a deep insecurity. No one at the party is shown as having such a concern. Whether you think the others are dilettantes who talk in pretentious nothings, or not, the reader is not made privy to this self-consciousness. If they all, to some extent, perform themselves, it is Otto who is concerned with nothing else than how he is seen by the other and why the other should be affected by his appearance. One can’t help but think that Otto believes that the image he presents contains some kind of immediate interest that reveals itself to the viewer. Later on, this is explored through the added layer of gesture.

When among people he did not know, Otto often took down a book from which he could glance up and note the situation which he pretended to disdain. (189)

Otto positions himself as an outsider, the camera eye observing the others going about their business, passing judgement on all he sees over the top of his book. Yet, Gaddis tells us that this is pre-meditated, pre-programmed behaviour, and, most importantly, performed behaviour. Yet, when we try to imagine the scene is the image not absurd? It evokes a child recreating adult behaviour that they have seen in the cinema. Before interrogating what is actually said, I can’t help but think that this is the key depiction of Otto as writer who is as concerned with performing the media image of a writer as he is with actually writing. It is as though Gaddis is pre-empting those American ‘New Journalists’ that emerge in the following decade (Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion - the tedium, my god, the tedium) who position themselves at a point where they are participant and outside observer at the same time, yet, all the time ‘writers’. When one reads these writers there is always a sense that they are aloof and above their subjects and that the writers themselves are investigators of a society that is made lesser-than by their investigation. Otto is even incapable of doing that in a genuine sense. He can only pretend to disdain because this is the crowd he wants to be a part of. He cannot create a position of superiority because they do not view him with any sense of curiosity. Otto cannot feel superior because he is not as genuine as Anselm, nor as creative as Stanley, nor as on the brink as Hannah.

Otto so believes that he deserves to be recognised in some aspect that, in each of these rejections, the reader feels embarrassment and perhaps a little pity on Otto’s behalf, but, as it continues it is clear that he is a prisoner of his own making. However, something essential happens towards the end of this chapter, he is misrecognised by someone and handed an envelope. It is this misrecognition, enacted now and setting the groundwork for its repetition as the novel continues, which will flip all of Otto’s pretensions on their head and lead him down the path to genuine experience beyond anything he is prepared for.

When I set out to write this issue I did not intend to focus entirely on Otto. Sometimes these things just naturally occur as an accident of writing, the word limit I set, and my fairly loose approach to planning. I hope that what I have ended up writing here is of some use to you, intrepid readers. Changing my plan from focusing exclusively on Anselm in the bonus issue, I will be using that as an opportunity to take a look at the rest of the cast much more broadly. After I have finished this first volume of, The Recognitions, I will be doing a general house-keeping issue where I will bring up elements of each chapter which were missed the first time around, if you have any questions please send them to me in direct messages and I will make a note of them for answer there. Thank you for reading.

Ryan Sweeney (@thecautiouscrip/insta: teawithzizek)

Youtube: www.youtube.com/@RealityOnToast

Patreon: patreon.com/RealityOnToast