Losing Friends, Influencing No One - Issue #1 Who Was William Gaddis?

The difficulty of biography and reading

In the past I’ve resisted partly because of the tendency I’ve observed of putting the man in the place of his work, and that goes back more than thirty years; it comes up in a conversation early in The Recognitions. (William Gaddis, The Paris Review, 1987)

Most writing you will encounter (especially that found in popular avenues of information access such as YouTube videos) pertaining to William Gaddis (1922-1998) will start in the same place, Jonathan Franzen’s 2002 New Yorker essay: ‘Mr. Difficult: William Gaddis and the Problem of Hard Books’. And while Mr. Franzen’s essay is essential to understanding contemporary receptions to Gaddis’s work, and an interesting introduction in its own right, I believe that the essay is worth a whole issue to itself. The other in-road authors like to take is to start from the critical and commercial failure of The Recognitions (1955), Gaddis’s subsequent disappearance, and the eventual triumph the triumph of his 1975 National Book Award winner, JR. This is convenient, because it gives Gaddis a nice tragedy and triumph arc. Yet, in writing this introduction, I find the former approach too detached from what it is I want to achieve, and the latter account insufficient in the face of an artist who believed that revelatory power of the work of art was paramount over the life of its creator. It is then my duty to find some way of shepherding the reader towards the key question: Who is William Gaddis and why should I write about him?

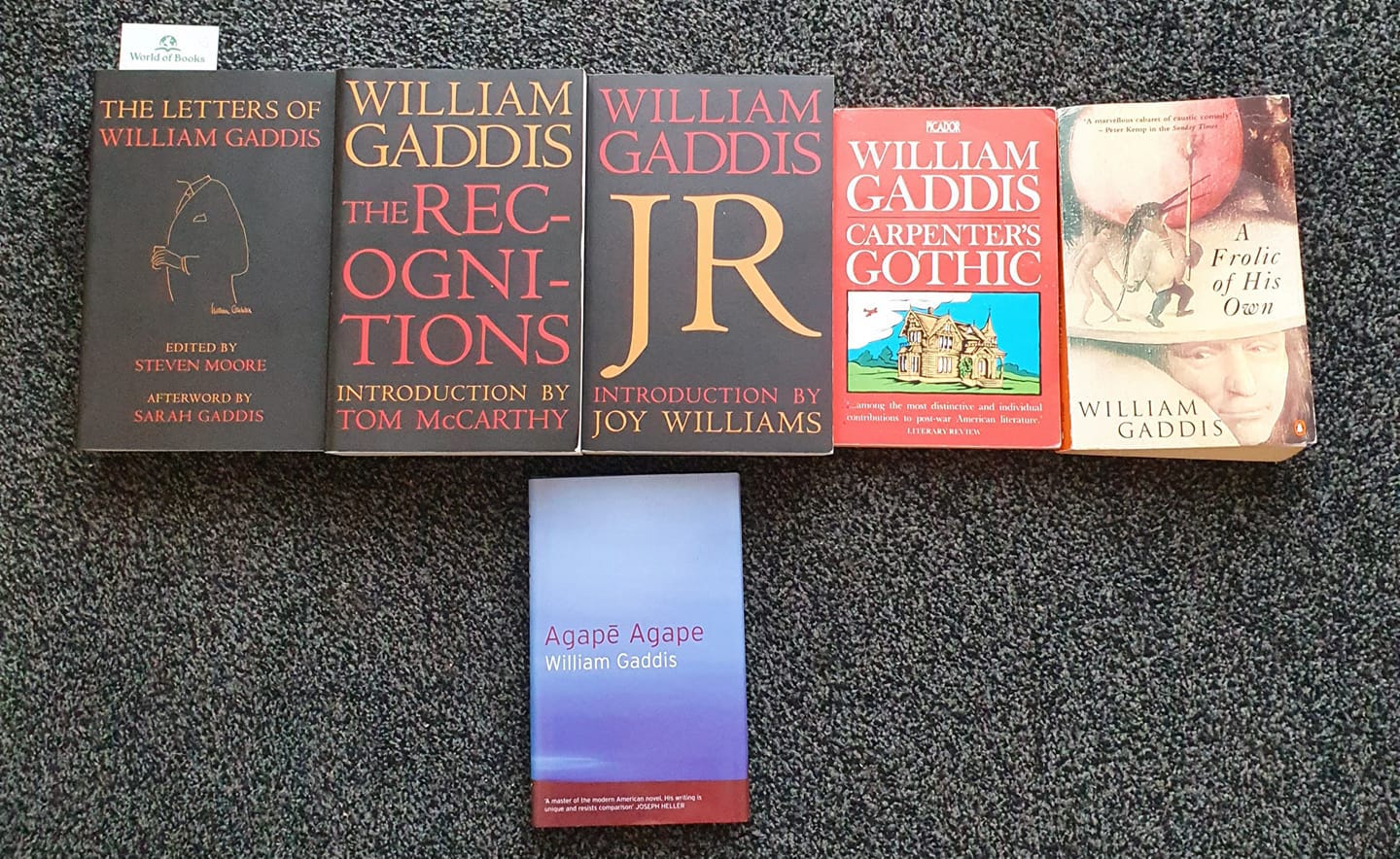

It seems to me that, in a 21st century world where so little challenging literature is read at all, Gaddis may well be completely off the radar to anyone existing outside of a graduate school or the deep dark corners of online literary culture. With this in mind, a short primer is in order. I have to consider that some readers of this may be complete neophytes into the Gaddis-sphere and are starting from a base level zero knowledge. That’s good! I think Gaddis would appreciate you most of all. The first thing that must be understood about William ‘Bill’ Gaddis is that he would not appreciate the effort I am making here. In fact, he would find the idea of introducing his work through introducing him to be stupid and a waste of everyone’s time. I can only ask his forgiveness then when I tell you that: William Gaddis was a 20th century novelist who published four works in his lifetime (The Recognitions (1955), JR (1975), Carpenter’s Gothic (1985), and A Frolic of His Own (1994)) and two posthumous works (Agapē Agape (2002), and The Rush For Second Place: Essays and Occasional Works (2002)). He is often labelled as ‘pretentious’ and ‘overly obtuse’ by the critical class and yet, the 2,500 or so pages he left behind are hailed by the post-war American writers as amongst the most influential. This is about as much as I am willing to say on the matter of biography. What must be understood about William Gaddis is that William Gaddis wants William Gaddis to be completely incidental to the work of William Gaddis. Fans of Thomas Pynchon, to a somewhat more extreme degree, will understand exactly what I mean. I’m not trying to be cute when I write this, I am simply trying to express the fundamental difficulty of Gaddis, biography, and the reading of art. This issue is something which will begin here and continue throughout because, in Gaddis’s work, it is introduced from the beginning and continues throughout.

Gaddis asks in, The Recognitions, and later in an interview with Zoltán Abády-Nagy: ‘What’s any artist but the dregs of his work?’ What, indeed? And yet, I’m far from the only person to note that there are elements of the entire corpus which resemble the biographical details I’ve encountered. To this Gaddis told Dalky Archieve:

‘The question of autobiographical sources in fiction has always seemed to me one of the more tiresome going, usually what simply amounts to gossip and about as reliable, not that we don’t all relish gossip.’

The rehashing of gossip is the very thing I hope to avoid as I undertake the gargantuan task which lay before me. I am certainly sensitive to the fact that the moment you become aware of certain biographical details it can then be very difficult to liberate your reading of the text from them. These notions then make it easy for one to arrive at blanket statements and readings which are ultimately useless to us in understanding either art or artist. Slapping simple answers onto difficult text is the kind of intellectual suicide that keeps me awake in terror at night. If one is looking for an easily digestible summary and diluted distillation of novels that they heard about on a ‘hardest books of all time’ list, then I’m afraid this isn’t going to be the place for you. And, while I will be drawing a lot from The Letters of William Gaddis (2013) and various other sources, I will not be pushing towards a biographical reading of any of these texts. We are not aiming for the dregs, but for the rich, full bodied tones of the art as it exists on the page.

Sadly, even to summarise Gaddis’s life in the manner that I would like to, by pointing out the significance of the two essential dates, imposes a reading onto the texts. This is unavoidable, and, as I dive back in against my best instincts, I hope you can forgive me.

William Gaddis was born in 1922. 1922 remains significant as the year of the publication of, Ulysses, and, The Waste Land. Two years after, Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), and, thirteen years before perhaps the most significant parallel Gaddis’s art, Walter Benjamin’s, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935). He dies in 1998, the year of Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, one year after Thomas Pynchon’s true masterpiece, Mason & Dixon (1997), and two years after David Foster Wallace publishes, Infinite Jest (1996) to immediate worldwide acclaim. It would be too great a cliché to say that Gaddis’s life encompasses the entirety of 20th century. Being alive and living while other people also produce great things is no great achievement, and such an accolade also belongs to, William Gass, John Barth, Susan Sontag, John Hawkes, and so many more. Where Gaddis stand out, to me particularly, is that he seems to encompass, internalise, and predict all of this. Much like Nabokov, he is a writer who picks up the loose ball and reimagines where we can go with it and what we need to do to take it there. His work is an intervention. An intervention against the art industry, against car crash Capitalism, against religious conmen, and against the spiritual death in the American Century. It takes the literature which has come before and gives it new life, a new form, and demands that it have something to say about the world to come. He does this again, and again, and again. When we ask how he achieved this, a lot of people who know will point to his sardonic tone, his wit, his Swiftian sense of critique through irony, and the freedom with which he dismantles the established novelistic forms like his Modernist forefathers. Yet, much like Nabokov, at the very heart of the journey is a love for life and for the expression of life through art. This is what elevates the whole endeavour above a nasty, masturbatory, teasing, game. As will be elucidated (I hope) throughout this journey, Gaddis is, in all of his contradictions, someone who strove to solve the problem of humanity in the 20th century. Now, in the 21st century, 102 years after his birth, it is time to return to his work.

In his outstanding piece of writing on The Recognitions, ‘Fire the Bastards!’ (1962), which I will be discussing in greater depth on the Patreon, Jack Green claimed: ‘before the mass public I know of no great novel that was permanently defeated by the enemies of art.’ I suppose, if you asked me to summarise why I have decided to undertake this project, then I would say that it is to cast my lot against the eroding tide of art’s enemies. Gaddis has been, in the academic literary world, canonised, and in that sense he has been saved from a permanent defeat. And yet, I feel as though there is still work to be done. In the Internet Age, one which seems to have produced a whole new economy devoted to stealing your attention, it seems the difficulty of preventing the loss of great literature only grows by the day. Great literary accomplishment which is not, and cannot be, integrated into the mainstream curriculum (which includes so few novels written after the Second World War) remains in great danger of falling from minds being colonised to bend towards the pleasures of mass culture. It is with this growing anxiety that I will write about Bill Gaddis. If any of these novels shall fall into the hands of the strange and the nonconforming, then I wish them well and say godspeed and good luck!

I hope this project will justify itself and serve as a small piece in the furthering of the legacy of art which has affected me on a most profound level.

Ryan Sweeney (@TheCautiousCrip / Insta: teawithzizek)

For bonus material such as explanations of the sources used in this issue, check out my Patreon: patreon.com/RealityOnToast For $5 you can have access to a whole other essay I wrote on ‘Fire the Bastards!’ and the problems with John Berger’s review of, The Recognitions