Losing Friends Influencing No One - Issue #3 Reading The Recognitions: Chapter I - The Spanish Affair

Fraudsters, Friars, Calvinists, and Camilla

Note on the text: This reading of The Recognitions will be using the 2020 New York Review Classics (NYRB) edition of the text. All page number references will refer to this edition. The recommended way to approach this blog is to read the chapter yourself, first, and then come back and read this. Of course you may read it however you like, but I will be starting with a synopsis which will inevitably contain spoilers. This is not intended as a replacement for Steven Moore’s (brilliant) annotations, but as another tool to help unlock this difficult book, and to further add to the discussion of William Gaddis’s work. For specific references, please consult https://www.williamgaddis.org/recognitions/I1anno1.shtml

Chapter I - Synopsis:

Gwyon, a New England Calvinist reverend, and his wife, Camilla set sail for Spain onboard the Perdue Victory. The ship’s doctor, unfortunately, is a fraudster, the money counterfeiter known as Mr Sinisterra. When Camilla is taken ill with appendicitis, Sinnisterra does everything he can to save her life but she dies because of his crime. After the ship docks in Spain, Sinisterra is arrested, and Gwyon is left in search of a place to bury the body of his wife. In the town of San Zwingli, Camilla is buried in the Catholic rite. As news of this reaches the US, Gwyon’s family and parishioners are scandalised and concerns over Gwyon’s spiritual state begin to grow. After Camilla is interred, Gwyon begins a period of wandering around Spain. He spends some time in a strict Catholic monastery where he is taken ill and, in the dead of night, is awoken by a vision of what will be his final encounter with his departed love. Leaving the monastery, he returns to America, but not before he collects a number of religious items of a deeply un-Protestant nature, including a Barbary Ape named Heracles. Returning to his son (and the novel’s protagonist), Wyatt, as well as his deeply puritanical Aunt May, it is clear that Gwyon is now no longer the same man that sailed to Spain. Gwyon has grown more concerned with the study of ancient religions than he is with actually living in the present. Aunt May grows more and more appalled by the things he says and the stories he tells Wyatt. Wyatt, without much parental oversight, begins to take an interest in painting and drawing, and makes copies of the Bosch and Breughel paintings that his father brought back from Europe. In an accidental act of symbolic violence, Wyatt kills a wren and, horrified by his own actions, is unable to take responsibility for the deed. As Gwyon becomes more non-conformist in his thought, Wyatt is struck down by a terrible illness which modern medicine can’t solve. Taking matters into his own hands, the reverend sacrifices the Barbary Ape in a pagan ritual and Wyatt recovers. While Wyatt isn’t aware that the ritual has taken place, a rift between father and son grows greater and greater. The years pass and it becomes clear that Wyatt’s heart is not with the seminary, but with his art. He drops out of divinity school and travels to Europe to study painting. The letter his father receives describing this change of fortune is torn up and scattered into the wind.

Characters -

Major: Gwyon, Wyatt, Camilla, Aunt May

Minor: Sinisterra, Town Carpenter, Janet, Heracles, Various minor figures in the Spanish section

The first chapter of, The Recognitions, is a bit of an unwieldy beast at first glance. It stretches itself over approximately fifteen years and two continents, it contains two sickness-induced hallucinations, and the allusions to obscure texts and religious symbolism fly thick and fast. It is not in the scope and remit of this blog to break down every reference, and I recommend having Steven Moore’s annotations (available on williamgaddis.org) open for anything that strikes your curiosity. What we can do, however, is attempt to crack into the events and show how the novel is functioning at this early stage. Through exploring the inner workings of this first chapter, I hope to elucidate its mysteries and aid anyone making their way through it for the first, or one hundred and first, time(s).

The novel opens with the epigraph, ‘Nihil cavum sine signo apud Deum’ (In God, nothing is empty of sense). This quote by Saint Irenaneus (130-202 c.e.) refers to a metaphysical position in which the meaning of all things formulate and resolve themselves around a transcendental being. Setting aside the religious significance to the early-Christian ideas the novel explores, for one moment. In impressing this position onto the novel before it begins, Gaddis is making a promise to the reader. It is a promise that, for all of the novel’s difficulty, it is not without a controlled sense. He wants us to know that, while the novel may initially confound, it is under his control, and that through application of our faculties we will be able to interpret the sense bestowed on it by this higher power (either that author-as-god, or God in whatever conception of that you have). As we explore the rest of the chapter, this statement becomes increasingly more significant. The characters are at the mercy of events which do not resolve themselves into obvious meaning. Camilla dies and both Gwyon and Wyatt suffer paranormal visitations, but they aren’t delivered to knowledge by them. The doctors that treat Wyatt move in nonsensical ways and seem to achieve nothing, but the sacrifice of an ape seems to cure the boy. The narrator discusses the act of God metaphorically, and then tells us then describes an event as the literal action of God (‘God boarded the Purdue Victory and acted’ (10)). Gaddis guides us towards not merely to accepting its strangeness as strangeness, but to attempt to come to a sense of the events. Just in case this idea of guidance wasn’t immediately understood, Gaddis invokes Goethe’s Faust II, in the chapter epigraph: ‘What is it, then? / A man is being made’. This is taken from the scene in which Mephistopheles and Faust witness the birth of the Homunculus which guides them through Classical Walpurgisnacht. Yet, one can’t also ignore the way in which ‘a man is being made’ can refer to multiple possibilities. Aside from the obvious, the allusion to the creation of the novel itself, it presents the novel as a possible bildungsroman about Wyatt, or the chapter as the creation of the new Gwyon, who enters and exits as two different men. Before we have even begun the novel proper, Gaddis is pointing us towards a progression that will lead us from no knowledge to knowledge even if it may seem without sense. In doing so, he also invites us to explore how the characters undergo this same transformation, how they are made men by the events of the novel.

At the start of the narrative, we’re brought into the funeral of Camilla in action:

‘Even Camilla had enjoyed masquerades, of the safe sort where the mask may be dropped at that critical moment it presumes itself as reality. But the procession up the foreign hill, bounded by cypress trees, impelled by the monotone chanting of the priest and retarded by hesitations at the fourteen stations of the Cross (not to speak of the funeral carriage in which she was riding, a white horse-drawn vehicle which resembled a baroque confectionary stand) might have ruffled the shy countenance of her soul, if it had been discernible.’ (9)

This evocative introduction establishes, in its first sentence, a key thematic element of the novel, the masquerade. In this instance, the funeral, with its ornate performance is the mask which stands between the observer and the reality of death. The authentic experience of the death is obscured by the need to imbue it with a ritualistic appeal to the transcendental aims of the Catholic faith. The masquerade is the metaphor for the dichotomy at the centre of the novel, the real and the fake, and the way in which various masks blur the boundary between the two. The presentation of the funeral reinforces this. Notice how alien the ritual is presented with its ‘monotone chanting’, and the constant stops at the stations of the cross (an act itself a counterfeit of a legendary event in order to capture some of its spiritual significance). Note, that the narration emphasises the existence of a ‘safe sort’ of masquerade. This implies the existence of a masquerade which is not ‘safe’, a masquerade in which the mask may never be dropped and a return to reality becomes impossible. The Catholic funeral is not, according to the narrator, the ‘safe sort’ of funeral. The funeral is the masquerade from which the central object never returns.

This sense of Camilla’s death being a boundary line between some ‘safe’ starting position and the obscured and unreal aftermath is somewhat explicit in the description of her death.

‘Before the mass supplications for souls in Purgatory had done rising from the lands now equidistant before and behind, he had managed to put an end to Camilla’s suffering and to her life.’ (11)

This leads us onto another reoccurring motif throughout the chapter, that of the voyage and the compulsion to partake in one. Camilla dies in transit. She dies on the ‘equidistant’ point between one space and another. This guarantees that which we know from Homer’s Odyssey, that it is impossible to return home the same person who left. The ‘impulse’ (10), as Gaddis describes it, for Gwyon to expand his boundaries has done so irrevocably. What is perhaps most strange, and which I’m sure most readers will pick up on, is that we are essentially given no information about Gwyon before this change other than he was a reverend who has an interest in travel. In a more conventional novel, perhaps we would expect the death of the mother/wife figure to come either off-page or as the dramatic climax to an introductory chapter or section, to which the rest of the novel would be about the parallels in the changed circumstance. Yet, here the death is our starting point. It is the true voyage which Gwyon and Wyatt will undertake and the event which both will continue to run from. Gwyon is so damaged by the event that he is described as such:

‘He had, by now, the look of a man who was waiting for something which had happened long before.’ (13)

This signals the retreat. A counter-voyage, if you will, Gwyon begins his long journey into the past. Time will continue to pass him by in its forward propulsion as he continues to search for a return to the thing which has already been and gone and become unreachable. In his sickness, when he envisions Camilla’s return, this idea is emphasised again:

‘He stood there unsteady in the cold, mumbling syllables which almost resolved into her name, as though he could recall, and summon back, a time before death entered the world, before accident, before magic, and before magic despaired, to become religion.’ (17)

The crux of why Gwyon becomes so consumed by research is here, clear as day. He believes that by going far enough into the past, into its strange arcana, that he can defeat death and summon back Camilla in some aspect. This is possibly what he’s referring to when, at the end of the chapter, he tells Wyatt that he must finish the painting: ‘finish it, or she will be with you […] or she will be with you always’ (63). The negation of the potential life he could have had with Camilla had they not travelled to Spain is contained, metaphorically, within the unfinished painting. The absence of Camilla consumes Gwyon and he recognises, in the unfinished painting as reflection of that absence, that it will in some way consume Wyatt too . Because of this absence, neither Gwyon nor Wyatt are able to achieve a sense of resolution amidst this all consuming missing presence. Note how Gaddis describes this relationship on page 31:

‘The two of them, father and son, grew away from her in opposite directions.’ (31)

The ‘her’, in this instance refers to the puritanical Aunt May, and if she represents the traditional pathways usually undertaken by their family line, and Gwyon is undergoing a voyage into the past, then it is Wyatt who is moving into the uncharted territory of the future. Wyatt is fleeing from the presence potential of the life that never was through a process of forward momentum and a rejection of the past (and a rejection of much more as we progress through the novel). He does this because the safety of the narrative of the family as it had existed for generations has been completely detonated by the traumatic loss of the mother. The reality of the spectre death has entered the collective psyche of the family and destroyed all of the internal mythology propping it up; (the familial line of reverends overseeing a small congregation). When Aunt May dies, Gwyon gives: ‘the last truly Christian sermon he had ever read.’ (45) It is as simple as this, the point that tied the twin elastic bands of Gwyon and Wyatt towards any sense of the normal family unit that existed pre-Camilla’s death has been removed and they are free to fly through the air in their respective directions. Gwyon, into the past, and Wyatt, into his unknowable future.

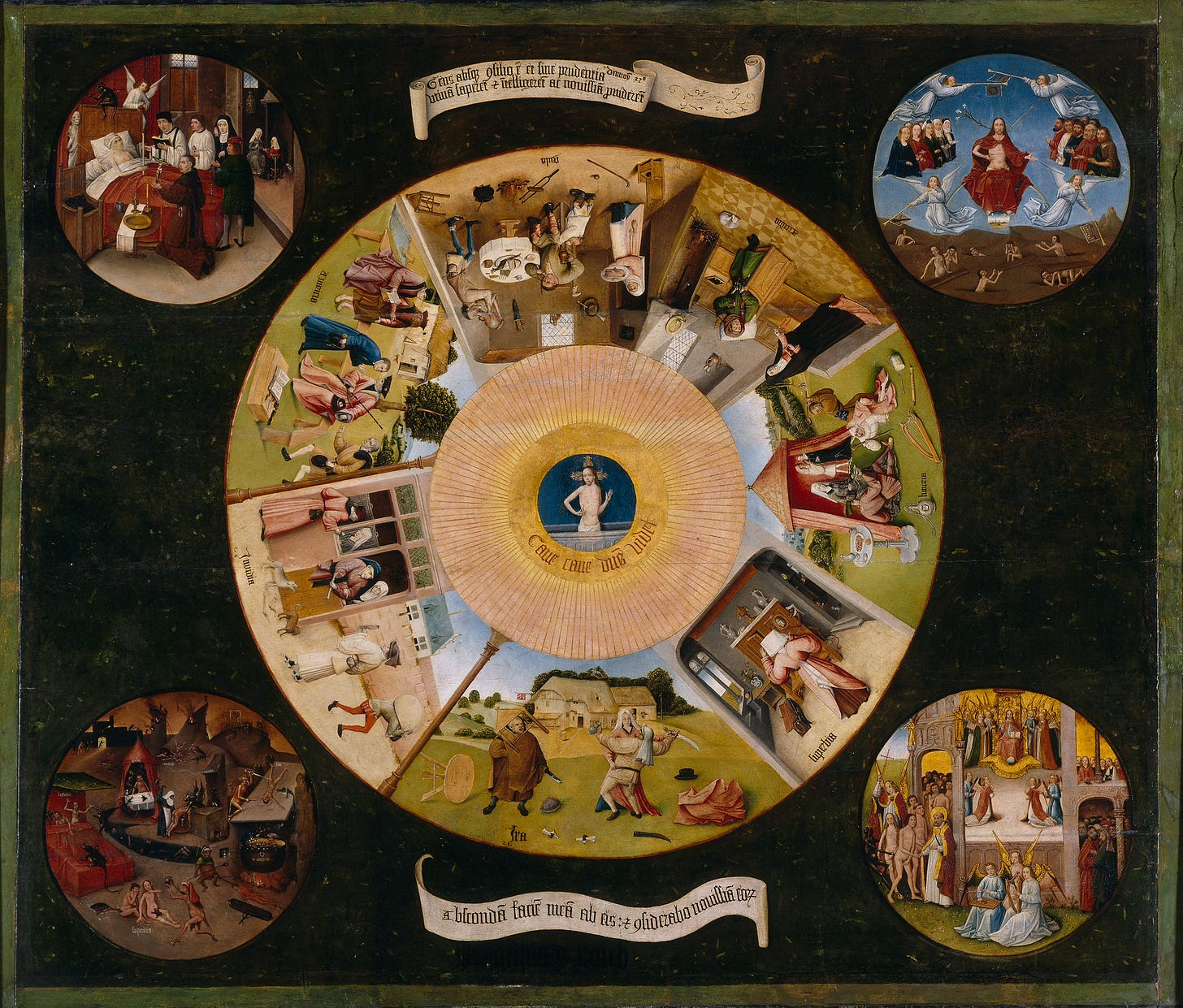

The essential object of Wyatt’s story arch is also introduced in this chapter, that being Hieronymus Bosch’s The Seven Deadly Sins. A mandala-like painting that Gwyon brought back from Europe and which he has kept as a table. Alongside another painting by Breughel, the young Wyatt spends much of his adolescence creating copies of this Bosch. In fact, of all the work he does, it is only these copies that he is able to complete.

‘Most were copies. Only those which were copies were finished. The original works left off at that moment where the pattern is conceived but not executed, the forms known to their author but their place daunted, still unfound in the dignity of the design.’ (56)

All of his originals, perhaps due to his aunt’s protestation that creating one’s own art is a sinful disrespect of God, remain incomplete. Many of his original attempts during her lifetime are created and destroyed in secret. Yet, an alternative explanation might be that the original painting always contains the potential for perfection until it is completed, once it is completed and perfection is unattained it can never aspire towards it again. The copy, the forgery, has an obtainable perfection, it merely has to reproduce the original exactly, including its imperfections. ‘Still the copies continued to perfection, that perfection to which only counterfeit can attain, reproducing every aspect of inadequacy, every blemish on Perfection in the original.’ (58) When he absconds to Europe, he takes these paintings with him (the Bosch, the Breughel, and the incomplete mother) for further study. Forgery and the notion that, ‘To sin is to falsify something in the Divine Order’ (38), is essential to how, The Recognitions, functions. As the novel continues, it will be revealed just how this inability to create the new and the savant skill at reproducing the old will lead to a spiritual ruination. This psychic block - the inability to produce a completed new artwork - is a direct result of the absent mother. Because Wyatt cannot bring himself to complete the portrait of his mother, he is haunted by its incomplete presence, and this prevents him from completing anything else. The reproductions are safer, they don’t offer a threat to his incomplete self. To complete the painting, as Gwyon tells him, would be to free himself from his mother. Because he can’t allow that, he succumbs to the sin of falsification whether he is aware of this or not.

At this point, Wyatt is not actually committing forgery. He is producing copies and imitations. Yet, it is interesting how this manifestation of the traumatic loss of his mother also ties him back to the man who is responsible for the death. Sinisterra is the money forger who lies about being a doctor to hitch a ride on the Perdue Victory and who is unable to perform the surgery which would have saved Camilla’s life. Sinisterra is a morally complex man, as will be explored later. He commits the crime, yet he is deeply contrite about it. He does not associate this incident at all with his work as a forger, this happened at God’s hands - not Sinisterra’s. In fact, his work as a forger is as much an art to him as painting is to Wyatt. The methods he uses invoke Rembrandt, the great Dutch painter, which mirrors Wyatt’s fascination with Rembrandt’s Belgian predecessors. It is almost as though there is a constant return to this central moment which all of the characters are unable to detach themselves from. Even unconsciously, unknowingly to the characters, the reverberations of Sinisterra’s actions (which he passes onto God), re-emerge throughout the novel in multiple different guises. The forger, either as an independent agent or moved by the hand of God, has brought death into the world of Gwyon and Wyatt leaving them to become a man who fights death and a man who refuses to confront real death so he hides himself in forgery.

Although the novel has multiple story threads, the central voyage of, The Recognitions, is a voyage through the mandala of Wyatt’s life to see if he can overcome the trauma of this chapter and find a complete whole-self. Ultimately, Gwyon is destroyed by the death of Camilla, and his voyage in the pursuit of a mythic defeat of death only leads to what the modern world perceives as madness. Wyatt is not yet at his lowest point, but the seeds of what will come later have been sown in these first 60 pages. As we continue through the novel, I implore the reader to keep in mind Wyatt as a character driven by an absence, and an attempt to resolve that absence, even if he isn’t consciously aware of it.

Further discussion of The Recognition’s first chapter will be taking place on Patreon, including an exploration of its more esoteric ideas and the infamous monkey sacrifice. If you are interested please consider subscribing, £5 a month will get you access to each issue’s bonus essay as well as all of my research notes. You can also message me directly there if you have any further questions.

BONUS ESSAY: Reading The Recognitions: Chapter I - Mystical Mystery Tour ($5/£4.50 no sub required) https://www.patreon.com/posts/issue-3-reading-116230866?utm_medium=clipboard_copy&utm_source=copyLink&utm_campaign=postshare_creator&utm_content=join_link

Patreon: patreon.com/RealityOnToast

Ryan Sweeney (@thecautiouscrip / insta: teawithzizek)