MOVIE REVIEW: Memoir of a Snail (dir. Adam Elliot, 2025)

'Childhood is the greatest season; it ends quickly but everyone deserves one.'

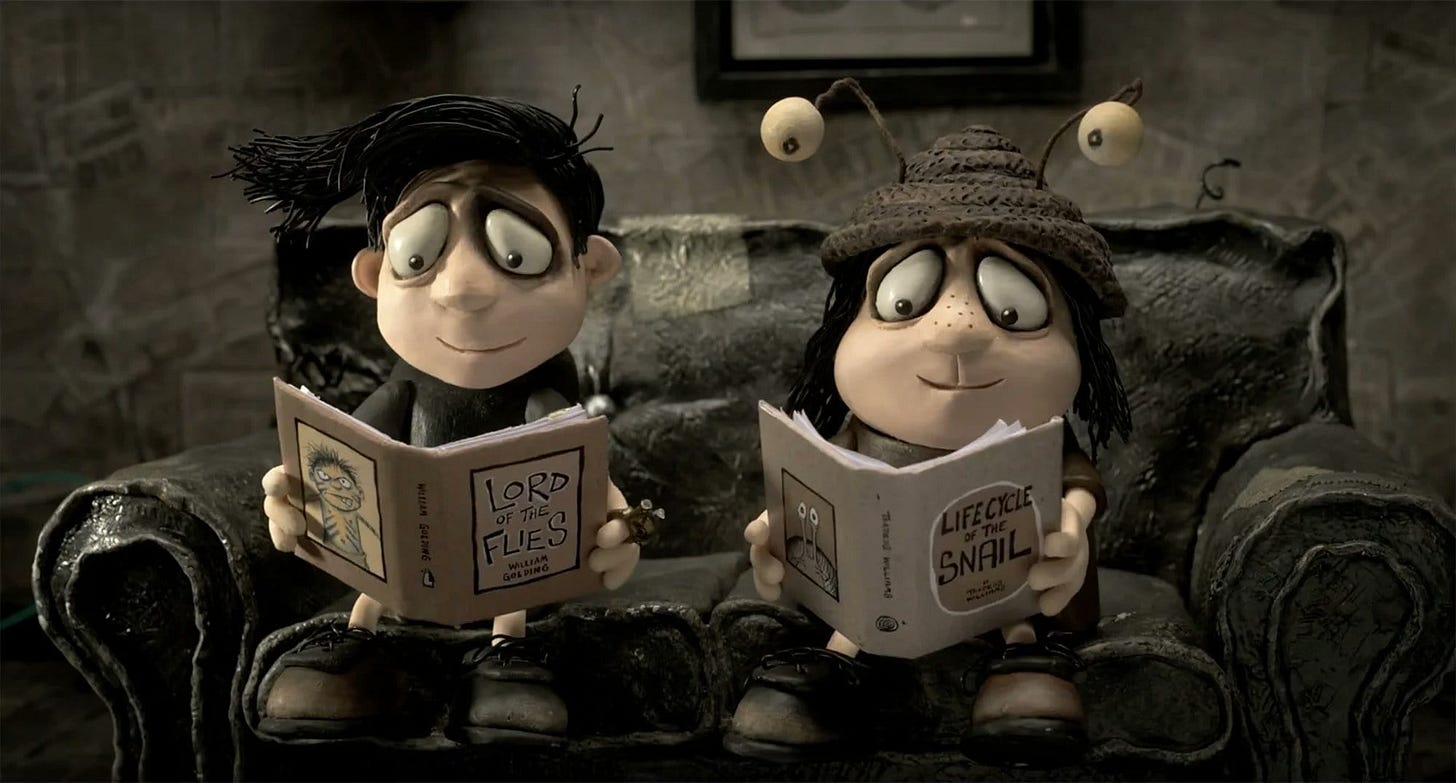

Memoir of a Snail, the latest feature from claymation heartbreak maestro, Adam Elliot (Mary and Max, Harvie Krumpet) is obviously a mini-marvel of a film. A painstakingly handcrafted world that exists on an aesthetic axis between the ghoulish creatures inside Lon Chaney’s mind and Shaun the Sheep after an economic collapse, the love of craft on display is beyond reproach. While the story is compelling and more than capable of moving even the most austere viewer, I find myself wondering if the film sacrifices its greater potential in the service of sentimentality.

The film follows the life of the lonely Grace Pudel (Sarah Snook) as she recounts her life to her pet snail, Sylvia, following the death of her only friend, Pinky (Jacki Weaver). We learn that Grace is a twin, separated and sent to live in different states by the Australian foster care system following the death of her father. Her brother, Gilbert (Jodi Smit-McPhee), is sent to live with an intensely religious family who shave their children’s heads and force them to work on an apple orchid. The two write to one another and plan to reunite someday, but Gilbert’s surroundings only work to strain this dream. Grace, fostered by swingers in Canberra, retreats further into herself. She adopts her mother’s interest in malacology (the study of snails) but begins to take it to an extreme degree the more isolated she feels in society. She hoards snail memorabilia, covering every inch of space in her life with their shells. Her loneliness is somewhat relieved when she meets the elderly, Pinky (a name given to her as the result of a grizzly accident). Pinky is a free-spirit, a woman who has lived a life of adventure and doesn’t care what anyone thinks of her. Things appear to get better for Grace as her friendship with Pinky, yet she cannot escape the hardships of her life and her social isolation. A marriage comes and goes in tragedy. And Pinky too passes after a short battle with dementia. Grace, alone, must come to terms with her place in the world and learn to move forward through life.

I have purposely avoided spoilers and purposely obscured some details in the above recap, but I believe that it is an adequate description of the film’s events to ground the rest of this review. As Memoir of a Snail unfolded and the details of Grace’s life, especially her early life, were divulged to the audience, I was quite taken by how the film portrays the origins of trauma. Grace’s childhood is sad, yes. Her mother dies in childbirth. She is born with a cleft-lip. She almost loses her life on the operating table were it not for a blood donation from her brother. Her father is an alcoholic paraplegic street-performer. She is bullied relentlessly by other children. And, yet, there is a tremendous amount of love. There is love from her father, and her brother who will defend her to the death. There is the love of literature, and the love of The Two Ronnies, and the love for snails. Unhappiness stems, in fact, from the material conditions of poverty and the lack of systems in place to adequately protect two vulnerable children and their disabled father. With such starkness we are presented a world in which two children are simply left to figure it out for themselves. As Grace and Gilbert are raising themselves with very little parental or societal oversight their strange interests are able to fester into unhealthy pathologies. Grace’s malacology, a method of retreat into a de-personalised existence. One which calls out to her dead mother for connection while simultaneously providing a soothing compulsion. Gilbert becomes a pyromaniac, obsessed with visions of his future as a fire-breathing street performer. It is a hobby which is completely unchecked by any adult until his matches are confiscated by his ruthless foster mother. For a film which is fundamentally about trauma and the trauma of very real, very serious events, to say that the foundations of these later incidents and the pathologies that created them were formed in the social neglect of childhood feels very significant. In avoiding the more standard story of the child being physically or emotionally abused by a parent, teacher, or adult in their life and, instead, focusing on the behavioural problems which emerge when children are allowed to fall through the cracks and saying that it is those same behavioural problems which manifest in later mental health issues feels more radical than it should. What it does is highlight the issues that come from our continued social atomisation. Because Gilbert and Grace are left in an apartment with a disabled parent, who himself requires social care, these issues are allowed to grow unchecked. There is no village to raise these children, in fact there is no social community outside of small units at all (as highlighted by the foul language of motorists throughout the film).

The most significant development of this idea occurs when Grace and Gilbert’s father dies and the two of them are separated. It is a damning indictment of the entire childcare system that such an event would have to take place (and yet we know that such a thing has occurred many times historically), and the horror of the separation is that the grounds for its supposed necessity is that ‘no one wants to adopt twins, especially not ones as weird as us’. This feels like a complete rejection of any social obligation we might have to protecting children who are not alone. It commodifies the child, turning them into an abstract object potential foster parents can pick and choose from like items in a supermarket instead of human beings with needs which must be given priority beyond categories like ‘cuteness’, ‘normalcy’, or (in the case of Gilbert) ‘labour value’. What does it say about the society we have created if we can allow ourselves to believe that separating twin orphan children is in any way acceptable. Such a moment amplifies the behavioural issues present in both Grace and Gilbert. As Gilbert isn’t around to protect Grace, she becomes more isolated which leaves her vulnerable to bullying, abuse, exploitation, and ultimately severe depression. As Grace is not around to balance Gilbert he becomes more rebellious, leaving him more vulnerable to physical abuse from his foster parents. The two children are separated, living on opposite sides of Australia, and there are no arranged meetings or social services check ins. They have yet again been left to fall through the cracks and are left vulnerable by neglect-by-ignorance.

Where I bang my head against the film (which is not to say that I did not enjoy the film, quite the opposite) is the way the film resolves this beautifully fiery social critique. Not to spoil the events of the film’s final third for anyone who might be interested in watching it, Memoir of a Snail, settles for a message of the individual needing to pick themselves up and move on. It repeats the Kierkegaardian message of ‘life is viewed backwards but must be experienced forward’, Grace puts her past behind her, lights it in a fire pit, and forges a new path forward. This is a noble sentiment, yet I wonder if it is adequate to deal with the bigger questions raised by the text. I question if the film needed to show a greater reintegration into society than the small victories achieved in the end and the good paid forward. Perhaps this is too much for a film operating on the very personal scale Memoir of a Snail is. Yet, I can’t help but think that I’d love to have seen a film with this much anger towards the social world fight for an end that is not merely individual peace.

Memoir of a Snail is a success. An adult animated drama of incredible quality and craftsmanship. I enjoyed my time with it, and ultimately my criticism of the film may well be minor when compared to the many areas the film triumphs in. I give it a hearty recommendation and commend everyone involved in its production.

Ryan Sweeney (@thecautiouscrip/insta: teawithzizek